An enigma of love in La Pedrera

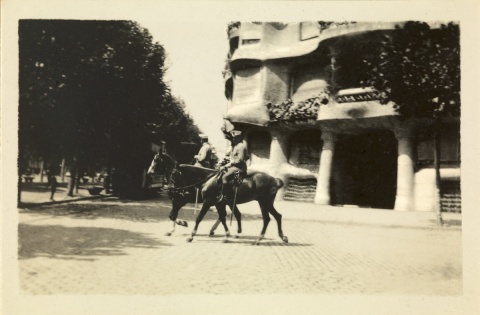

In 1906 the architect Antoni Gaudí watched as the foundations were laid on the site that would eventually become home to the icon of Modernisme, the Casa Milà, (La Pedrera), in Barcelona’s Passeig de Gràcia. That same year, the celebrated Catalan writer Eugeni d'Ors’ published his first glosses in La Veu de Catalunya newspaper that he would include in his novel Teresa, La Ben Plantada,[1] the stunningly beautiful and extremely admired enigmatic muse, who came to symbolise the Noucentisme and the spirit of the Renaixença[2]. These two milestones, which marked the blossoming of two antagonistic and conflicting artistic and philosophical movements, had one thing on common: my great grandmother, Teresa Mestre de Baladia.

Two years later Ramon Casas, the foremost modernista artist, painted my great grandmother in secret. When Eugeni d'Ors[3] set eyes on the portrait of the woman who had inspired his ‘Ben Plantada’, he proclaimed the work to be the cornerstone of the Noucentisme[4], and immediately embarked on a bold initiative to set up, as a complement to the existing Gallery of illustrious Catalans, a ‘Gallery of Catalan beauties’ in which my great grandmother’s portrait would be the first acquisition. The poet Joan Maragall embraced the initiative and rallied society to make it a reality.

But, as so often happens in this country, the venture was foiled. Aunt Ramona, the extremely affluent and equally overweight bourgeois matriarch of the Baladia family, outraged by artistic frivolities, had Teresa confined to the stately home in Argentona, remodelled with castle-like pretentions by the architect Josep Puig i Cadafalch. Notwithstanding, the Museu d'Art de Catalunya petitioned Ramon Casas for the portrait of La Ben Plantada, who, in turn, requested the permission of Teresa’s husband (my great grandfather), known to me as ‘el Padrí, who assented to request. However, to avoid any conflict, Casas insisted that the museum should include a clause to the effect that the portrait of Teresa would not form part of any portrait gallery.

Unable to bear Aunt Ramona’s punishment, the beautiful and admired Teresa stole away into the night on horseback, leaving her spouse and three offspring – Gip, Niní and Ninus – with Ramona. She moved into a house the couple owned in Barcelona, believing her husband and children would follow her. Although my grandfather was madly in love with her, Padrí did not move. Aunt Ramona told him that she would have him disinherited him if he returned to his wife. Months passed and nothing happened. All the letters that Teresa sent to Padrí and their children were intercepted by Ramona, who was bent on maintaining discretion, secrecy and the good name of the family.

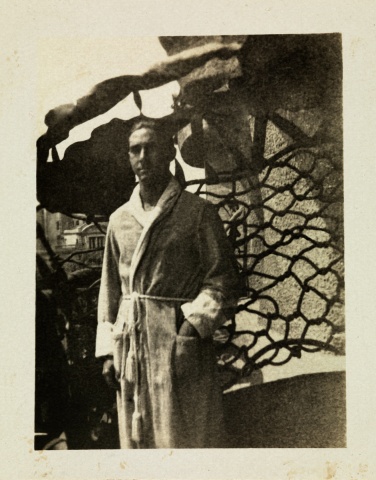

Meanwhile, Teresa found herself moving between the various family properties in Barcelona, one of which was in La Pedrera where, according to family legend, she lived out her stormiest days. La Pedrera apartment, though 300 square meters in size, was the couple’s pied a terre, a small, convenient and centrally located place used to sleep over after a night-out at the Liceu, the Palau de la Música, the theatre or a party, when it was too late to return to little Isabeline palace at Riera de Mataró or to the stately home in Argentona.

Aunt Ramona forbade Teresa to visit her children, whom together with my great grandfather, she held captive in Argentona. Teresa was in despair. And then a young, attractive admirer by the name of Josep Pijoan came to her aid and consequently fell in love with her. Pijoan was a multifaceted cultural activist and founder of the Institute of Catalan Studies, and one of the most promising men of his generation. Even the powerful Puig i Cadafalch, Padrí’s intimate friend, after hearing of the scandalous affair with Teresa declared war on him. The notorious liaison between Teresa Baladia and Josep Pijoan, which became known as “the spectacular and mysterious flight”, rocked the foundations of the Catalan society of the Belle Epoque. We will probably never know what really happened, since the affair remains an enigma to this day. No-one knows where they stayed, when they left, where they went or, more damning of all, whether she was became pregnant by Pijoan while they were together in Barcelona. To avert a scandal, both Teresa and Pijoan avoided giving any more information than that which had already got out, and when they did, it was to add even more confusion.

My great grandmother Teresa never returned home to her husband. She had two sons by Pijoan and travelled the globe with him, always in the company of prominent figures of their day. She passed away in a New York hospital while her close friend, Andrés Segovia, played guitar at her bedside. Pijoan later married his secretary, who was much younger than he, and the couple settled in Geneva. My great grandfather Padrí, heartbroken, remained in the stately home in Argentona like a monk in seclusion. Many years later I learned that he had continued paying his wife’s membership fees of the Centre Excursionista de Catalunya up to the day he received news of Teresa’s death – perhaps in memory of the happy times they spent together in the Pyrenees and the Alps. Moreover, after learning of his wife’s passing, Padrí wore a black tie for the rest of his days.

La Pedrera apartment remained virtually unused. Its legatee, Gip, already owned a main floor apartment, also in Passeig de Gràcia, on the corner of carrer de València, as well as a tower at the top of the same building that he had as an “artist’s studio”, though it seems he only ever used it to throw parties. Niní moved into a house at the foot of Vallvidrera. My grandfather Ninus, while pursuing his studies in Barcelona, lived on a property of his fiancée, Rat de Ferrater Llorach, in Sant Gervasi. After marrying, they moved to Mataró to be near the factory. Only my great grandfather, very occasionally, stayed overnight in La Pedrera, to immediately rush back to Argentona the next day. Nonetheless, Padrí continued to pay the rent on the apartment until the early thirties. It seems too long a time to keep an apartment that no-one used. Another enigma.

I have a nagging feeling that perhaps Padrí kept La Pedrera apartment, in the hope that someday, perhaps unexpectedly, his cherished Teresa, his eternal Ben Plantada, would return there.

[1] The term ‘ben plantada’ means ‘firmly rooted’, but in the context of the book’s title it also carries a suggestion of ‘handsome woman’.

Contributor:

- F. Javier Baladia

Javier Baladia (Barcelona, 1965) is the author of the novel Antes que el tiempo lo borre. Recuerdos de los años de esplendor y la bohemia de la burguesía catalana (Editorial Juventud, 3rd edition 2010) that describes the private life of his family, the Baladias, and takes us back to the golden age of a cosmopolitan and refined elite. Javier Baladia was co-scriptwriter of the documentary film Barcelona, antes de que el tiempo lo borre, directed by Mireia Ros in 2010, which won the 2012 Gaudí Award for Best Documentary.