A Student at La Pedrera

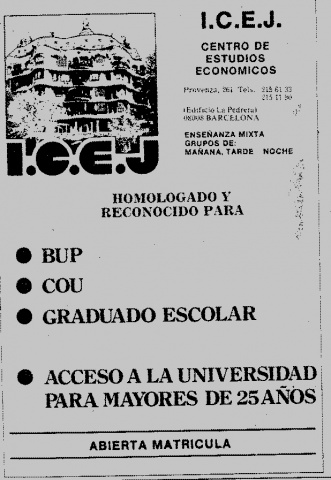

I never lived in La Pedrera, but between 1980 and 1984 I received my upper secondary school education at the ICEJ Academy, which took up the entire ground floor from carrer de Provença to Passeig de Gràcia.

It seems like only yesterday, but many years have passed and everything has changed so much.

The ICEJ was a private academy that taught secondary education and university access courses for students over 25 years of age. Originally located in another premises in carrer Provença, the ICEJ Academy (whose initials stood for “Instituto de Ciencias Económicas y Jurídicas”) gave reinforcement lessons to students of Law and Economics, but in the early seventies it moved to La Pedrera, where it stayed until the late eighties, shortly before the build-up to Olympic Games.

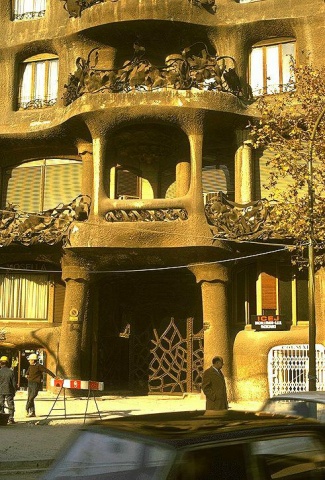

I first visited La Pedrera in 1980 to hand in my basic education grade record before beginning the school term. My first impression upon entering the building on Career de Provença was one of gloominess. It had never been refurbished and everything was dreary, the ornaments and inscriptions on the ceilings had been damaged and the building’s overall appearance, particularly the interior, looked neglected and run down, much like most of the buildings in the Eixample district before the “Barcelona, get dressed up!” campaign was launched by Barcelona City Hall, ahead of the 1992 Olympic Games.

The new school term began in September and I quickly got to know the building. La Pedrera was like an enchanted castle: a labyrinth of nooks and crannies to be discovered. I did my first year in the classroom on the corner of Passeig de Gràcia. The wooden floor, originating from the times of Gaudí, had darkened with the passage of time. There was not a single right-angle in the walls or ceilings, and each door and each frame was different, unique, as were the door handles and knobs. The walls were painted from the floor to mid-height in dark brown, and from there to the ceiling in white. The unglamorous lighting consisted of fluorescent tubes, suspended from the tall ceilings by chains, which we would sometimes use as a net to play volley ball with balls of screwed up aluminium foil in which we brought our sandwiches. I recall how I would relax during the break, my head still abuzz with numbers, mathematical, chemical and physics formulae, by staring at the ceilings, which reminded me of lunar landscapes filled with craters and small mountains.

There was little tourism at that time, only in spring did we see a few Japanese visitors with their Nikon and Canon cameras taking photos left, right and centre; those of us who studied at the academy must be in lots of Japanese photo albums.

The school also had an apartment on the fourth floor. To get to there, you had to take the lift, which, though old and shabby, had a unique marquetry. The lift could not be used to go down, and you risked the concierge’s wrath if you did, so we had to take the dark stairwell, which seemed more like a cavern. I never had lessons on the fourth floor, but I do remember an incident when the tenants on the carrer de Provença side of the building, in great alarm, called the director, because some students were throwing paper aeroplanes out of the windows of the famous building, their tails in flames could been seen gliding down to the street.

The academy also had a bar in in a semi-basement premises in the carrer Provença courtyard that was run by the gym teacher and his wife. It was a tiny but cosy place, at affordable prices for the students. One time the gym teacher had to kill a rat there amid the screams of the female students.

There was also the basement, which was accessed via a spiral ramp leading to a tiny underground square, which, it was said used to be, when the building was first opened, the location of the coach house. We also heard that in more recent times it had served as a venue for a hippy flea market, though I can’t verify this. The fact is that the school director would park his Mercedes down there. It was very dark and the ramp – in the purest Gaudí style – curled around itself like a snake. There were mirrors on the walls, apparently to guide the few drivers who would park their cars down there, and it stank of cobbler’s glue because there used to be a shoe repair shop on one corner of La Pedrera, and the smell and the noise of the machines were permanent. The basement also housed the school’s auditorium, the physics, chemistry and biology laboratories as well as a technical drawing classroom, where I agonized with my Rotring pens over drawings in order to pass the subject. The auditorium was where the school festivals were held. I remember the much talked-about Carnival of 84 or 83, with some students performing the Trinca’s song “las Hermanas Sister”. I do recall someone taking photos; it’d be interesting to find them. The laboratories were well equipped; the biology lab had a skeleton into whose mouth students would place cigarette butts, much to the anger of the teachers.

The school also had a music room, which was in the small courtyard at the rear of La Pedrera. A prefabricated aluminum structure, it was a long room equipped with speakers where music lessons were taught to first-year secondary students and battles using sticks of chalk as ammunition were fought out.

La Pedrera was as different and versatile as the Passeig de Gràcia of the time, with both a residential and business atmosphere – very appealing and welcoming, and very human. There was a bingo hall with a neon lights fixed to the building’s facade; the shoe repair shop; the Parera clothes store, which only recently closed; a print shop; a bar serving “tourist menus” where some of the teachers ate, and, most endearing of all, there was Mr Solé’s corner store.

Mr Solé’s corner store was on the corner of carrer Provença. It was an old shop, its shelves stacked with every kind of product and drink, where products were sold that couldn’t be found anywhere else in Barcelona, such as Sali milk. Mr Solé was a short bald man with plastic framed glasses with milk-bottle lenses that made his eyes seem huge. The shop counter contained baskets filled with chupa-chups, chewing gums and sweets painstakingly arranged, and all on sale for 5 pesetas. On another counter there was a huge glass jar filled with bread rolls with which he would make you a cheese and ham sandwich. Mr Solé would tell stories about the building to anyone who was interested. He had run the shop for more than 40 years, from before the civil war. He claimed that only the ground floor and the first floor were made of stone, while those above were made of cement... he also explained that he employed his shop assistants from school for orphans, and that one of them had begun as an apprentice and worked for him until he retired. Mr Solé grew old and eventually began to confuse coins; if you bought 5 pesetas of sweets, he returned you change of twenty-five or fifty pesetas. The shop also succumbed to the Olympics.

And so four years rolled by with fun, long hours of classes, first-loves and many anecdotes, like the snowball fight we had after the small snow fall of ’83 on the corner of Passeig de Gràcia. That school turned out some of the great men of Barcelona society and a couple of marriages as well.

On one occasion one of the door knobs came away in my hand as I opened the door. It was an original, designed by Gaudí, and no two were alike. It was like a twisted piece of brass. There was no-one around at the time and I was tempted to keep it, but my the idea weighed on my conscience and I handed it to the manager, who showed me a drawer full of knobs, and told me he kept them because they were unique works of art. He thanked me for having returned it.

This is my personal account of La Pedrera. I have no photographs of the interior of the building. It’s astonishing: the students didn’t take photographs inside La Pedrera – it was the time before digital cameras, perhaps because for us it was more like a prison where we spent many hours having lessons. We were the generation of 66 of la Pedrera.

Juan Bernardo Nicolás Pombo. Former student of ICEJ. 1980-1984.

Contributor:

- Juan Bernardo Nicolàs Pombo